By Peter Hossli

In those days TV images flickered into America’s living rooms in black and white. Because of this, Nixon’s jacket color was virtually indistinguishable from the Chicago studio backdrop. Kennedy, on the other hand, was wearing a dark navy blazer, making him pop out on the TV screen with Nixon, vanishing into the background like a chameleon.

Not only this, Nixon also refused the application of makeup. As a result, under the studio lights, he looked pale, had sweat running down his face and appeared unshaven. Kennedy’s face had been powdered giving him a fresh and confident look in the eyes of 70 million viewers, constituting two thirds of all Americans who would be going to the polls in November.

The majority later argued that Kennedy had won the first-ever live TV debate between two presidential candidates, but not on the merits of making more astute points. Those having followed the debate over the radio for the most part, declared Nixon the winner.

Kennedy however, somehow just looked better. He was simply more telegenic. While Nixon did his best to step up his performance during the subsequent debates, his first impression stuck. Kennedy went on to defeat him by 120,000 votes in early November. Historians agree that the decisive moment in the election had been the first TV debate.

This anecdote is evidence of the degree to which US Presidential elections are waged in the media, however it isn’t always the person who makes the best impression in all of the media who is destined to win. It is usually the candidate with the best handle on the emerging technology of the day.

As was the case with Barack Obama, who made it to the White House in 2008 thanks to social media. Bill Clinton used cable TV to his advantage in 1992. In the thirties, Franklin D. Roosevelt spoke on the radio enabling him to hide his paralytic illness. John F. Kennedy, who was only 43 years old at the time, was the one to suggest the televised debates to the Vice President. While Nixon’s advisors cautioned their candidate, fearing the worst, he dismissed their warnings assuming his experience with radio would suffice.

Kennedy, however, had realized that TV is vastly different from radio. The day before the debate he opted to visit the studio, had the nuances of the cameras explained to him and took a good look at the backdrop. Richard Nixon stayed at home.

The following day Kennedy spoke directly into the camera, talking to the viewers as if he were right there in their living rooms. Nixon, more accustomed to radio debate, instinctively directed his gaze towards his opponent – and cataclysmically, away from the voters at home.

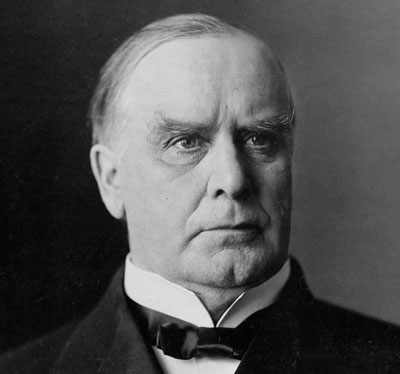

Photographs first appeared in American newspapers in 1897 and have been a mainstay ever since. The Republican presidential candidate, William McKinley, had impressively demonstrated their effect a year earlier. Travelling around the country he had his picture taken at every opportunity, either alone or in a crowd and had the photos printed on over 100 million flyers.

He spent 6 million dollars on this campaign; twenty times as much as his Democratic opponent.

However, his campaign workers did not distribute the flyers indiscriminately. McKinley’s political strategist, Mark Hanna, analyzed the electoral districts he needed to canvas in particular. Hanna invented a technique other strategists that followed would elaborate on for decades: targeted canvassing.

These were used to fill the commercial breaks in popular access prime-time soap operas. The ads used the same format as detergent commercials, making the product the hero, and turned the stern soldier into a jovial and accessible politician. His opponent considered this type of publicity too banal. The brilliant Adlai Stevenson passed on TV ads and lost the election.

Inheriting the Presidency after the Kennedy assassination in November 1963, Lyndon B. Johnson managed to secure his return to the White House with a new tactic, negative campaigning. In the now legendary «Daisy Girl ad» he portrayed Republican Barry Goldwater as a war monger, jeopardizing America’s idyllic world in the middle of the Cold War and bringing on the threat of an imminent nuclear winter.

For decades Americans almost exclusively watched terrestrial broadcasts via TV aerial. National television networks like ABC, CBS and NBC offered viewers series, sports and news. Cable networks played only a minor role in broadcasting for a long time, until a young governor from Arkansas entered the political arena.

Instead of buying expensive ad space on the big three networks, Bill Clinton aired his campaign commercials on cable TV in the 1992 election year. This allowed him to maximize airtime and target more specific geographic locations, right down to individual electoral districts thereby significantly reducing non-selective advertising losses. At the same time Clinton’s advisors recognized the multiplier effect of the still very new non-stop news broadcaster CNN. While opponents, George Bush and Ross Perot, complained about low TV ratings, Clinton often appeared on Larry King. His conversations with the CNN talk-master subsequently made headlines. It was Clinton who set up his first website in the middle of the 1996 election year. His opponent, Bob Dole, had nothing like that to offer and Clinton went on to celebrate his re-election.

Just four years later every candidate had his or her own website. They raised money online, took up a dialog with their constituents and found themselves able to communicate their messages outside the traditional media.

Barack Obama was nicknamed the «Twitter President», and rightly so. In the 2008 election year he expertly employed social media to boost his campaign. Utilizing the knowledge that young voters primarily communicate online, Obama spread messages on YouTube, published private photos from inside the campaign on Flickr and mobilized fans with short messages on Twitter. He had five times as many Facebook friends as his opponent John McCain.

The 2012 campaign will be mobile

Media use has become more mobile. Over 100 million Americans now obtain their information via smartphones and tablet computers like the iPad allowing news stories, Facebook and Twitter messages to reach voters faster than ever. You can even watch TV on mobile devices anytime.

In spring of 2011, the New York Times dubbed the 2012 Presidential elections a «mobile media event». Whoever gets the best handle on this trend will be elected president.

The candidates have programmed their websites for mobile devices with many of them producing their own apps. iTunes alone offers several dozen apps dealing with the election and while some have been launched by traditional publishing houses most have been created by independent journalists.