By Peter Hossli (text) and Johannes Krömer (foto)

It’s the hand that distinguishes humans from other animals. Only primates can touch their thumbs with each finger and have a free range of movement in positioning their hands. “The hand is independent and very precise,” is how Nelson Botwinick describes it.

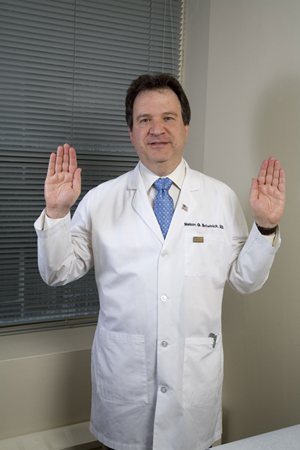

And he, more than anyone, is in a position to know. Over the past 20 years, the New York doctor has operated on more than 8,000 hands. He’s considered the best in his field. Every year since 1988, “New York Magazine” has ranked him as the top hand surgeon in the city. Why? Because he’s honest with himself and his patients. “You can only be the best if you concentrate exclusively on what you can do,” says Botwinick. He’s got a clenched stone fist on his desk. The 51-year-old talks in a high-pitched voice with a rapid-fire New York accent reminiscent of Woody Allen, but his gestures are calm and considered.

He picked this profession, he says, because it brooks absolutely no mistakes. “A careless person can never become a hand surgeon.” He has to be able to put in screws he can’t even see without the aid of a magnifier. When he drills a hole he can’t afford to be even half a millimeter off. “There are doctors that can’t handle that kind of stress,” says Botwinick, “so they go in for hip replacements, where there are larger tolerances.”

Simply put, he likes the pressure. He likes the sense of satisfaction that comes with knowing immediately that you’ve done the right thing. Whereas a doctor specializing in back pain can treat a patient for 20 years, Botwinick knows instantly whether his operation has been a success.

He loves the hand itself, respects it, and approaches it with great reverence. “It’s got everything,” he says: tendons, skin, bones, muscles. The hand is a sensory organ. People talk with it, clap hands when they meet. After the eyes, it is the second thing you notice when you first meet someone. A deformed hand stands out just as much as a deformed face. And we depend on our hands more than ever. We make more use of them than we did 20 years ago,” he says; “ to type, use our BlackBerry, and play videogames.”

Botwinick operates on between 10 and 12 hands a day. His work covers a broad spectrum: He removes tumors, does carpal tunnel operations, fixes breaks, and treats osteoporosis and inflamed tendons. Sometimes he amputates limbs or sews fingers back on. “I like it when I have a mixture of routine and complicated fractures,” is how he describes a good day in the operating room, a place where “I’m in complete control.” He doesn’t talk to anyone while he’s operating. He approaches even the simplest procedure as if it were the most difficult he had encountered in the course of his career. “I owe that to my patients,” he says. “If my attention wavers, there’ll be mistakes.”

Botwinick always has the same goal in view. He tries to preserve the three principal functions of the hand: spatial positioning, mechanics, and the application and control of force. Scratching your elbow is not the same as reaching for a needle or a jar of pickles. The three processes are run by three nerves. Sensation is transmitted from the hand to the brain. “But the hand isn’t perfect,” emphasizes Botwinick. “It ages, suffers wear and tear, and is exposed to risks.” Emergency room statistics at local hospitals show that there are more acute injuries to the hand than to any other part of the body.

Botwinick takes care to protect his relatively small hands. “I don’t do anything stupid.” Whereas most New Yorkers pick up bagels to slice them, he always uses a breadboard. “I wear gloves when I work in the garden or take a hot pan off the stove.”